The Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources (IANR) recognizes the importance of mentoring to career-long professional development.

Departments, schools, and divisions within IANR have established formal mentoring procedures for faculty members within those units. Those guidelines map onto the principles identified here.

While the early career stages are often the focus of mentoring initiatives, mentoring can assist faculty members throughout their careers. Mentoring may be particularly useful when navigating transitions in roles that require new skills, perspectives, and networks. For example:

- The skills needed to be a successful graduate student or post doc may need to be applied differently or augmented to be successful as an early career faculty member.

- The strategies used to be successful as an early career faculty member may or may not work to be successful as a mid-career and late-career faculty member.

- What works to be a successful faculty member may not work for being a successful administrator.

Mentoring Framework

IANR encourages team and network approaches to mentoring. The faculty member—often with the assistance of the unit administrator, mentor, or other facilitator—identifies their needs, their existing network of support, the gaps in that network, and how those gaps might be filled with formal or informal mentors. Mentoring is driven by the needs of the faculty member. Decisions about who functions as mentor, how many people are part of the mentoring team (including whether or not there is a team), and what the expanded mentoring network looks like should all be made with the unique needs of the faculty member in mind.

Mentoring map

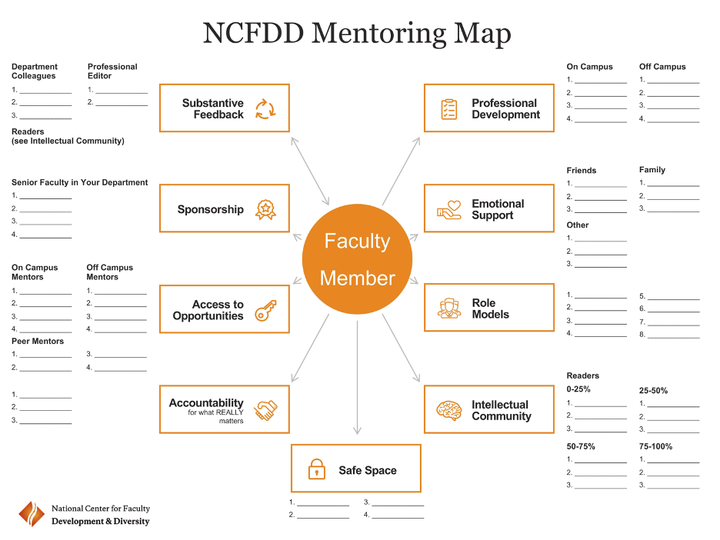

Most people have groups with which they identify and individuals to whom they look for support, encouragement, and guidance. Mapping these groups and individuals to the faculty member and with one another can help identify who meets various needs and gaps that exist. Unit administrators encourage faculty members to develop a mentoring map. The mentoring map is a tool that can help faculty members identify a) those who are part of their mentoring networks and b) gaps in their network that could be filled to meet needs.

NCFDD provides a webinar about mentoring maps and how to use them. The webinar is available for anyone who has an NCFDD account at https://www.facultydiversity.org/webinars/cultivatingyournetwork22. A guide for developing a mentoring map is found here.

Formal Mentoring

While the mentoring literature illustrates that informal and peer mentoring networks are more impactful to professional success than formal mentoring programs, a successful formal mentoring program lays a foundation for informal mentoring and peer mentoring. Formal mentoring helps to reinforce a culture of mentorship and to establish mentoring as normative. It would be a mistake to bypass formal mentoring expecting that informal and peer mentoring relationships will develop on their own. Getting formal mentoring right lays a foundation for the relationships that are central to informal and peer mentoring.

Guides, Primary Mentors, and Mentoring Teams

Faculty Guide

Every newly hired faculty member should be assigned a Faculty Guide prior to their start date. This assignment is made by the unit administrator. If the faculty member is also contributing to other units, this assignment is made in consultation with the relevant head, director, engagement zone coordinator, or program leader. It’s recommended that the Faculty Guide be someone who served on the search advisory committee for the search resulting in the faculty member’s hire, or someone contributing to the same disciplinary or programmatic area. The Faculty Guide is a point of contact for the newly hired faculty member. This is someone who will reach out to the new faculty member to welcome them and to offer to answer questions and/or support as they are approaching their start-date and shortly after they start.

Primary mentor

Within the first six months after their start date, a primary mentor should be identified for every faculty member. Faculty members should be actively engaged in identifying an appropriate mentor. This should be done in consultation with their unit administrator.

Mentoring team

A mentoring team consists of multiple people within the faculty member’s network who can meet needs by serving in formal mentoring roles. Those who are part of this team may or may not coordinate mentoring efforts. A mentoring team is particularly useful if a faculty member has various work responsibilities and/or disciplinary expertise that may not be able to be addressed by a primary mentor alone.

While there are advantages to a mentoring team, a mentoring team increases the complexity of mentoring. Care should be taken to create a formal mentoring configuration that will be tailored to the unique situation and needs of the faculty member.

Informal Mentoring

Both formal and informal mentoring are needs-driven. Formal mentoring is often characterized as professional and structured. While informal mentoring is also professional, it is often less structured and more likely to have friendship elements.

Informal mentoring is built on:

- An authentic relationship.

- Being accessible.

- Being compatible.

- Sharing standards for success.

- A recognition that it is also personal (and being okay with that).

Peer Mentoring

Peer mentoring is a natural progression from informal mentoring. As the mentee develops experience, expertise, and confidence, the hierarchical relationship between mentor and mentee flattens. Mentor and mentee begin functioning as peers who are learning from and supporting one another. Mentoring becomes more relational and reciprocal. Expansion of the peer network is characteristics of peer mentoring.

Possible helpful resources: